Author: Jon Awbrey

Differential logic is the component of logic whose object is the description of variation — for example, the aspects of change, difference, distribution, and diversity — in universes of discourse that are subject to logical description. A definition that broad naturally incorporates any study of variation by way of mathematical models, but differential logic is especially charged with the qualitative aspects of variation that pervade or precede quantitative models. To the extent that a logical inquiry makes use of a formal system, its differential component treats the principles that govern the use of a differential logical calculus, that is, a formal system with the expressive capacity to describe change and diversity in a logical universe of discourse.

A simple example of a differential logical calculus is furnished by a differential propositional calculus. A differential propositional calculus is a propositional calculus extended by a set of terms for describing aspects of change and difference, for example, processes that take place in a universe of discourse or transformations that map a source universe into a target universe. This augments ordinary propositional calculus in the same way that the differential calculus of Leibniz and Newton augments the analytic geometry of Descartes.

Cactus Language for Propositional Logic

edit

The development of differential logic is greatly facilitated by having a conceptually efficient calculus in place at the level of boolean-valued functions and elementary logical propositions. A calculus that is very efficient from both conceptual and computational standpoints is based on just two types of logical connectives, both of variable  -ary scope. The formulas of this calculus map into a species of graph-theoretical structures called painted and rooted cacti (PARCs) that lend visual representation to their functional structure and smooth the path to efficient computation.

-ary scope. The formulas of this calculus map into a species of graph-theoretical structures called painted and rooted cacti (PARCs) that lend visual representation to their functional structure and smooth the path to efficient computation.

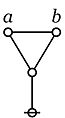

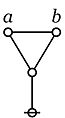

The first kind of propositional expression is a parenthesized sequence of propositional expressions, written as  and read to say that exactly one of the propositions and read to say that exactly one of the propositions  is false, in other words, that their minimal negation is true. A clause of this form maps into a PARC structure called a lobe, in this case, one that is painted with the colors is false, in other words, that their minimal negation is true. A clause of this form maps into a PARC structure called a lobe, in this case, one that is painted with the colors  as shown below. as shown below.

|

|

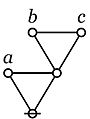

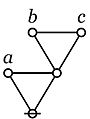

The second kind of propositional expression is a concatenated sequence of propositional expressions, written as  and read to say that all of the propositions and read to say that all of the propositions  are true, in other words, that their logical conjunction is true. A clause of this form maps into a PARC structure called a node, in this case, one that is painted with the colors are true, in other words, that their logical conjunction is true. A clause of this form maps into a PARC structure called a node, in this case, one that is painted with the colors  as shown below. as shown below.

|

|

All other propositional connectives can be obtained through combinations of these two forms. Strictly speaking, the parenthesized form is sufficient to define the concatenated form, making the latter formally dispensable, but it is convenient to maintain it as a concise way of expressing more complicated combinations of parenthesized forms. While working with expressions solely in propositional calculus, it is easiest to use plain parentheses for logical connectives. In contexts where ordinary parentheses are needed for other purposes an alternate typeface  may be used for logical operators.

may be used for logical operators.

Table 1 collects a sample of basic propositional forms as expressed in terms of cactus language connectives.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}a~\mathrm {implies} ~b\\[6pt]\mathrm {if} ~a~\mathrm {then} ~b\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/40560aef1c9e95e065b510c31bd7db4afe3f49dd)

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}a~\mathrm {not~equal~to} ~b\\[6pt]a~\mathrm {exclusive~or} ~b\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2d02b0d65d46d4082e8997c72fc33680a35ff074)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}a\neq b\\[6pt]a+b\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/46df96d2c6dc080dc2c82fb0599d183ff9fca93c)

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}a~\mathrm {is~equal~to} ~b\\[6pt]a~\mathrm {if~and~only~if} ~b\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b73fab73354e189f98ae65434b7e6fafdd365342)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}a=b\\[6pt]a\Leftrightarrow b\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d98dfb6783481c9924473cdcbe6443b05fdf6083)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {just~one~of} \\a,b,c\\\mathrm {is~true} .\\[6pt]\mathrm {partition~all} \\\mathrm {into} ~a,b,c.\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/03fdc28fb40ed9d39e46dffa433afe18cff4dfcf)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {partition} ~x\\\mathrm {into} ~a,b,c.\\[6pt]\mathrm {genus} ~x~\mathrm {comprises} \\\mathrm {species} ~a,b,c.\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/367a6152de188a4e4f2e75ad394e1a20cc175ad4)

|

|

The simplest expression for logical truth is the empty word, usually denoted by  or

or  in formal languages, where it forms the identity element for concatenation. To make it visible in context, it may be denoted by the equivalent expression

in formal languages, where it forms the identity element for concatenation. To make it visible in context, it may be denoted by the equivalent expression  or, especially if operating in an algebraic context, by a simple

or, especially if operating in an algebraic context, by a simple  Also when working in an algebraic mode, the plus sign

Also when working in an algebraic mode, the plus sign  may be used for exclusive disjunction. For example, we have the following paraphrases of algebraic expressions by means of parenthesized expressions:

may be used for exclusive disjunction. For example, we have the following paraphrases of algebraic expressions by means of parenthesized expressions:

|

|

|

|

It is important to note that the last expressions are not equivalent to the 3-place parenthesis

Differential Expansions of Propositions

edit

An efficient calculus for the realm of logic represented by boolean functions and elementary propositions makes it feasible to compute the finite differences and the differentials of those functions and propositions.

For example, consider a proposition of the form  that is graphed as two letters attached to a root node:

that is graphed as two letters attached to a root node:

Written as a string, this is just the concatenation  .

.

The proposition  may be taken as a boolean function

may be taken as a boolean function  having the abstract type

having the abstract type  where

where  is read in such a way that

is read in such a way that  means

means  and

and  means

means

Imagine yourself standing in a fixed cell of the corresponding venn diagram, say, the cell where the proposition  is true, as shown in the following Figure:

is true, as shown in the following Figure:

Now ask yourself: What is the value of the proposition  at a distance of

at a distance of  and

and  from the cell

from the cell  where you are standing?

where you are standing?

Don't think about it — just compute:

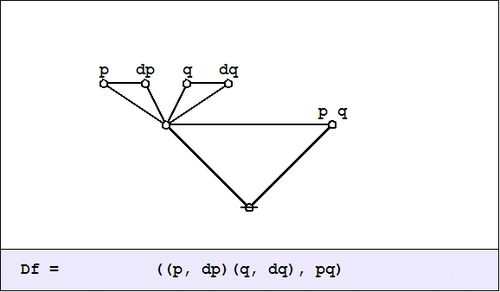

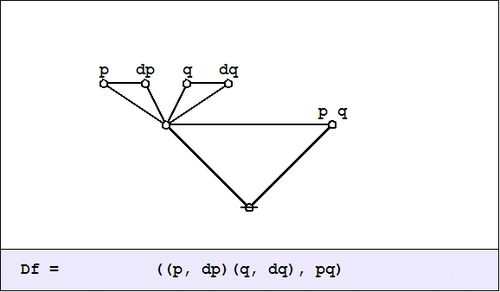

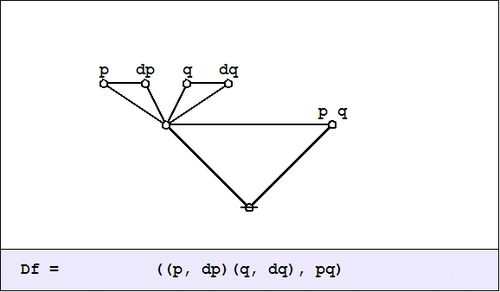

The cactus formula  and its corresponding graph arise by substituting

and its corresponding graph arise by substituting  for

for  and

and  for

for  in the boolean product or logical conjunction

in the boolean product or logical conjunction  and writing the result in the two dialects of cactus syntax. This follows from the fact that the boolean sum

and writing the result in the two dialects of cactus syntax. This follows from the fact that the boolean sum  is equivalent to the logical operation of exclusive disjunction, which parses to a cactus graph of the following form:

is equivalent to the logical operation of exclusive disjunction, which parses to a cactus graph of the following form:

|

Next question: What is the difference between the value of the proposition  over there, at a distance of

over there, at a distance of  and

and  and the value of the proposition

and the value of the proposition  where you are standing, all expressed in the form of a general formula, of course? Here is the appropriate formulation:

where you are standing, all expressed in the form of a general formula, of course? Here is the appropriate formulation:

There is one thing that I ought to mention at this point: Computed over  plus and minus are identical operations. This will make the relation between the differential and the integral parts of the appropriate calculus slightly stranger than usual, but we will get into that later.

plus and minus are identical operations. This will make the relation between the differential and the integral parts of the appropriate calculus slightly stranger than usual, but we will get into that later.

Last question, for now: What is the value of this expression from your current standpoint, that is, evaluated at the point where  is true? Well, substituting

is true? Well, substituting  for

for  and

and  for

for  in the graph amounts to erasing the labels

in the graph amounts to erasing the labels  and

and  as shown here:

as shown here:

And this is equivalent to the following graph:

We have just met with the fact that the differential of the and is the or of the differentials.

|

|

It will be necessary to develop a more refined analysis of that statement directly, but that is roughly the nub of it.

If the form of the above statement reminds you of De Morgan's rule, it is no accident, as differentiation and negation turn out to be closely related operations. Indeed, one can find discussions of logical difference calculus in the Boole–De Morgan correspondence and Peirce also made use of differential operators in a logical context, but the exploration of these ideas has been hampered by a number of factors, not the least of which has been the lack of a syntax that was adequate to handle the complexity of expressions that evolve.

Let's run through the initial example again, this time attempting to interpret the formulas that develop at each stage along the way. We begin with a proposition or a boolean function

A function like this has an abstract type and a concrete type. The abstract type is what we invoke when we write things like  or

or  The concrete type takes into account the qualitative dimensions or the “units” of the case, which can be explained as follows.

The concrete type takes into account the qualitative dimensions or the “units” of the case, which can be explained as follows.

Let  be the set of values be the set of values

|

Let  be the set of values be the set of values

|

Then interpret the usual propositions about  as functions of the concrete type

as functions of the concrete type

We are going to consider various operators on these functions. Here, an operator  is a function that takes one function

is a function that takes one function  into another function

into another function

The first couple of operators that we need to consider are logical analogues of the pair that play a founding role in the classical finite difference calculus, namely:

The difference operator  written here as written here as

|

The enlargement operator  written here as written here as

|

These days,  is more often called the shift operator.

is more often called the shift operator.

In order to describe the universe in which these operators operate, it is necessary to enlarge the original universe of discourse. Starting from the initial space  its (first order) differential extension

its (first order) differential extension  is constructed according to the following specifications:

is constructed according to the following specifications:

|

|

where:

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcc}X&=&P\times Q\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} X&=&\mathrm {d} P\times \mathrm {d} Q\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} P&=&\{{\texttt {(}}\mathrm {d} p{\texttt {)}},~\mathrm {d} p\}\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} Q&=&\{{\texttt {(}}\mathrm {d} q{\texttt {)}},~\mathrm {d} q\}\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e605ad19dd796627c5bfedfa779b03b1945ca1ed)

|

The interpretations of these new symbols can be diverse, but the easiest option for now is just to say that  means “change

means “change  ” and

” and  means “change

means “change  ”.

”.

Drawing a venn diagram for the differential extension  requires four logical dimensions,

requires four logical dimensions,  but it is possible to project a suggestion of what the differential features

but it is possible to project a suggestion of what the differential features  and

and  are about on the 2-dimensional base space

are about on the 2-dimensional base space  by drawing arrows that cross the boundaries of the basic circles in the venn diagram for

by drawing arrows that cross the boundaries of the basic circles in the venn diagram for  reading an arrow as

reading an arrow as  if it crosses the boundary between

if it crosses the boundary between  and

and  in either direction and reading an arrow as

in either direction and reading an arrow as  if it crosses the boundary between

if it crosses the boundary between  and

and  in either direction.

in either direction.

|

Propositions are formed on differential variables, or any combination of ordinary logical variables and differential logical variables, in the same ways that propositions are formed on ordinary logical variables alone. For example, the proposition  says the same thing as

says the same thing as  in other words, that there is no change in

in other words, that there is no change in  without a change in

without a change in

Given the proposition  over the space

over the space  the (first order) enlargement of

the (first order) enlargement of  is the proposition

is the proposition  over the differential extension

over the differential extension  that is defined by the

following formula:

that is defined by the

following formula:

|

|

In the example  the enlargement

the enlargement  is computed as follows:

is computed as follows:

|

|

|

Given the proposition  over

over  the (first order) difference of

the (first order) difference of  is the proposition

is the proposition  over

over  that is defined by the formula

that is defined by the formula  or, written out in full:

or, written out in full:

|

|

In the example  the difference

the difference  is computed as follows:

is computed as follows:

|

|

|

We did not yet go through the trouble to interpret this (first order) difference of conjunction fully, but were happy simply to evaluate it with respect to a single location in the universe of discourse, namely, at the point picked out by the singular proposition  that is, at the place where

that is, at the place where  and

and  This evaluation is written in the form

This evaluation is written in the form  or

or  and we arrived at the locally applicable law that is stated and illustrated as follows:

and we arrived at the locally applicable law that is stated and illustrated as follows:

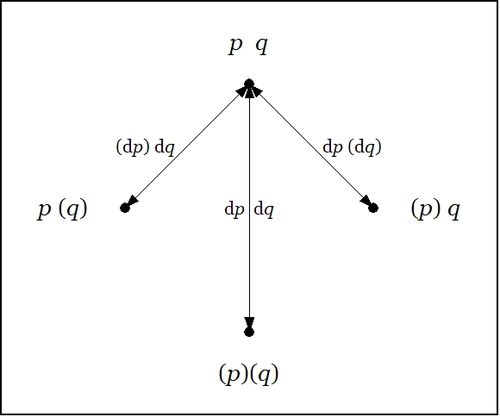

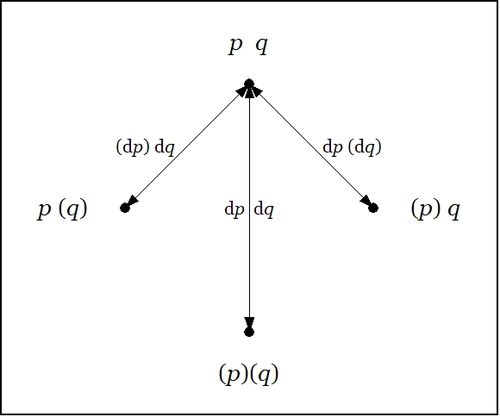

The picture shows the analysis of the inclusive disjunction  into the following exclusive disjunction:

into the following exclusive disjunction:

|

|

The differential proposition that results may be interpreted to say “change  or change

or change  or both”. And this can be recognized as just what you need to do if you happen to find yourself in the center cell and require a complete and detailed description of ways to escape it.

or both”. And this can be recognized as just what you need to do if you happen to find yourself in the center cell and require a complete and detailed description of ways to escape it.

Last time we computed what is variously called the difference map, the difference proposition, or the local proposition  of the proposition

of the proposition  at the point

at the point  where

where  and

and

In the universe  the four propositions

the four propositions  that indicate the “cells”, or the smallest regions of the venn diagram, are called singular propositions. These serve as an alternative notation for naming the points

that indicate the “cells”, or the smallest regions of the venn diagram, are called singular propositions. These serve as an alternative notation for naming the points  respectively.

respectively.

Thus we can write  so long as we know the frame of reference in force.

so long as we know the frame of reference in force.

In the example  the value of the difference proposition

the value of the difference proposition  at each of the four points in

at each of the four points in  may be computed in graphical fashion as shown below:

may be computed in graphical fashion as shown below:

The easy way to visualize the values of these graphical expressions is just to notice the following equivalents:

Laying out the arrows on the augmented venn diagram, one gets a picture of a differential vector field.

The Figure shows the points of the extended universe  that are indicated by the difference map

that are indicated by the difference map  namely, the following six points or singular propositions::

namely, the following six points or singular propositions::

|

|

The information borne by  should be clear enough from a survey of these six points — they tell you what you have to do from each point of

should be clear enough from a survey of these six points — they tell you what you have to do from each point of  in order to change the value borne by

in order to change the value borne by  that is, the move you have to make in order to reach a point where the value of the proposition

that is, the move you have to make in order to reach a point where the value of the proposition  is different from what it is where you started.

is different from what it is where you started.

We have been studying the action of the difference operator  on propositions of the form

on propositions of the form  as illustrated by the example

as illustrated by the example  that is known in logic as the conjunction of

that is known in logic as the conjunction of  and

and  The resulting difference map

The resulting difference map  is a (first order) differential proposition, that is, a proposition of the form

is a (first order) differential proposition, that is, a proposition of the form

Abstracting from the augmented venn diagram that shows how the models or satisfying interpretations of  distribute over the extended universe of discourse

distribute over the extended universe of discourse  the difference map

the difference map  can be represented in the form of a digraph or directed graph, one whose points are labeled with the elements of

can be represented in the form of a digraph or directed graph, one whose points are labeled with the elements of  and whose arrows are labeled with the elements of

and whose arrows are labeled with the elements of  as shown in the following Figure.

as shown in the following Figure.

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcccccc}f&=&p&\cdot &q\\[4pt]\mathrm {D} f&=&p&\cdot &q&\cdot &((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]&+&p&\cdot &(q)&\cdot &~(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]&+&(p)&\cdot &q&\cdot &~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\\[4pt]&+&(p)&\cdot &(q)&\cdot &~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2e79bd56d18729e4930c0365011748b45c5a7715)

|

Any proposition worth its salt can be analyzed from many different points of view, any one of which has the potential to reveal an unsuspected aspect of the proposition's meaning. We will encounter more and more of these alternative readings as we go.

The enlargement or shift operator  exhibits a wealth of interesting and useful properties in its own right, so it pays to examine a few of the more salient features that play out on the surface of our initial example,

exhibits a wealth of interesting and useful properties in its own right, so it pays to examine a few of the more salient features that play out on the surface of our initial example,

A suitably generic definition of the extended universe of discourse is afforded by the following set-up:

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{lccl}{\text{Let}}&X&=&X_{1}\times \ldots \times X_{k}.\\[6pt]{\text{Let}}&\mathrm {d} X&=&\mathrm {d} X_{1}\times \ldots \times \mathrm {d} X_{k}.\\[6pt]{\text{Then}}&\mathrm {E} X&=&X\times \mathrm {d} X\\[6pt]&&=&X_{1}\times \ldots \times X_{k}~\times ~\mathrm {d} X_{1}\times \ldots \times \mathrm {d} X_{k}\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/069ce164e0a22e555bcbd6ac68d29beb9f920050)

|

For a proposition of the form  the (first order) enlargement of

the (first order) enlargement of  is the proposition

is the proposition  that is defined by the following equation:

that is defined by the following equation:

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{l}\mathrm {E} f(x_{1},\ldots ,x_{k},\mathrm {d} x_{1},\ldots ,\mathrm {d} x_{k})\\[6pt]=\quad f(x_{1}+\mathrm {d} x_{1},\ldots ,x_{k}+\mathrm {d} x_{k})\\[6pt]=\quad f({\texttt {(}}x_{1},\mathrm {d} x_{1}{\texttt {)}},\ldots ,{\texttt {(}}x_{k},\mathrm {d} x_{k}{\texttt {)}})\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dbdbaa9f75fbc33bc0f3a4af7a5c5a4784370dae)

|

The differential variables  are boolean variables of the same basic type as the ordinary variables

are boolean variables of the same basic type as the ordinary variables  Although it is conventional to distinguish the (first order) differential variables with the operative prefix “

Although it is conventional to distinguish the (first order) differential variables with the operative prefix “ ” this way of notating differential variables is entirely optional. It is their existence in particular relations to the initial variables, not their names, that defines them as differential variables.

” this way of notating differential variables is entirely optional. It is their existence in particular relations to the initial variables, not their names, that defines them as differential variables.

In the example of logical conjunction,  the enlargement

the enlargement  is formulated as follows:

is formulated as follows:

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{l}\mathrm {E} f(p,q,\mathrm {d} p,\mathrm {d} q)\\[6pt]=\quad (p+\mathrm {d} p)(q+\mathrm {d} q)\\[6pt]=\quad {\texttt {(}}p,\mathrm {d} p{\texttt {)(}}q,\mathrm {d} q{\texttt {)}}\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aa02c09d04ffd6ea427e5698eaab8a10b69b2cc5)

|

Given that this expression uses nothing more than the boolean ring operations of addition and multiplication, it is permissible to “multiply things out” in the usual manner to arrive at the following result:

|

|

To understand what the enlarged or shifted proposition means in logical terms, it serves to go back and analyze the above expression for  in the same way that we did for

in the same way that we did for  Toward that end, the value of

Toward that end, the value of  at each

at each  may be computed in graphical fashion as shown below:

may be computed in graphical fashion as shown below:

Given the data that develops in this form of analysis, the disjoined ingredients can now be folded back into a boolean expansion or a disjunctive normal form (DNF) that is equivalent to the enlarged proposition

|

|

Here is a summary of the result, illustrated by means of a digraph picture, where the “no change” element  is drawn as a loop at the point

is drawn as a loop at the point

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{rcccccc}f&=&p&\cdot &q\\[4pt]\mathrm {E} f&=&p&\cdot &q&\cdot &(\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt]&+&p&\cdot &(q)&\cdot &(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~\\[4pt]&+&(p)&\cdot &q&\cdot &~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt]&+&(p)&\cdot &(q)&\cdot &~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/510843e94088ee8beaba85f0f9a1880dc2461deb)

|

We may understand the enlarged proposition  as telling us all the different ways to reach a model of the proposition

as telling us all the different ways to reach a model of the proposition  from each point of the universe

from each point of the universe

To broaden our experience with simple examples, let us examine the sixteen functions of concrete type  and abstract type

and abstract type  A few Tables are set here that detail the actions of

A few Tables are set here that detail the actions of  and

and  on each of these functions, allowing us to view the results in several different ways.

on each of these functions, allowing us to view the results in several different ways.

Tables A1 and A2 show two ways of arranging the 16 boolean functions on two variables, giving equivalent expressions for each function in several different systems of notation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{0}\\[4pt]f_{1}\\[4pt]f_{2}\\[4pt]f_{3}\\[4pt]f_{4}\\[4pt]f_{5}\\[4pt]f_{6}\\[4pt]f_{7}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/24b5936bb9b07a16b0ce25bbcd9d15a0c4f66e30)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{0000}\\[4pt]f_{0001}\\[4pt]f_{0010}\\[4pt]f_{0011}\\[4pt]f_{0100}\\[4pt]f_{0101}\\[4pt]f_{0110}\\[4pt]f_{0111}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1086c49ca9e6d18beaeff20f2eb0e311a7acd83b)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}0~0~0~0\\[4pt]0~0~0~1\\[4pt]0~0~1~0\\[4pt]0~0~1~1\\[4pt]0~1~0~0\\[4pt]0~1~0~1\\[4pt]0~1~1~0\\[4pt]0~1~1~1\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8a45856ada62c19bd47d8a9e2e84300e15cae37c)

|

(q)\\[4pt](p)~q~\\[4pt](p)~~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~~(q)\\[4pt](p,~q)\\[4pt](p~~q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/965c46c20583777f355f9a8b7099c67f97017b9c)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}{\text{false}}\\[4pt]{\text{neither}}~p~{\text{nor}}~q\\[4pt]q~{\text{without}}~p\\[4pt]{\text{not}}~p\\[4pt]p~{\text{without}}~q\\[4pt]{\text{not}}~q\\[4pt]p~{\text{not equal to}}~q\\[4pt]{\text{not both}}~p~{\text{and}}~q\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6f0b92763fe3c9466d147da7df17eb6b7eb09a88)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}0\\[4pt]\lnot p\land \lnot q\\[4pt]\lnot p\land q\\[4pt]\lnot p\\[4pt]p\land \lnot q\\[4pt]\lnot q\\[4pt]p\neq q\\[4pt]\lnot p\lor \lnot q\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ab7eba4008c32ee46ac0d3a035b2cfef49241332)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{8}\\[4pt]f_{9}\\[4pt]f_{10}\\[4pt]f_{11}\\[4pt]f_{12}\\[4pt]f_{13}\\[4pt]f_{14}\\[4pt]f_{15}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0f86aaf9bba3aaf4ee8497c5bb429033137800fa)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{1000}\\[4pt]f_{1001}\\[4pt]f_{1010}\\[4pt]f_{1011}\\[4pt]f_{1100}\\[4pt]f_{1101}\\[4pt]f_{1110}\\[4pt]f_{1111}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/785a3875c73bc8f293427312f1a3c550b0334640)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}1~0~0~0\\[4pt]1~0~0~1\\[4pt]1~0~1~0\\[4pt]1~0~1~1\\[4pt]1~1~0~0\\[4pt]1~1~0~1\\[4pt]1~1~1~0\\[4pt]1~1~1~1\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/633c2e421ef40928e11cb873552d67cc9bb418de)

|

)\\[4pt]~~~q~~\\[4pt]~(p~(q))\\[4pt]~~p~~~\\[4pt]((p)~q)~\\[4pt]((p)(q))\\[4pt]((~))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8edba2d2c333fd96e9a58e32dcebff041eecd6c2)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}p~{\text{and}}~q\\[4pt]p~{\text{equal to}}~q\\[4pt]q\\[4pt]{\text{not}}~p~{\text{without}}~q\\[4pt]p\\[4pt]{\text{not}}~q~{\text{without}}~p\\[4pt]p~{\text{or}}~q\\[4pt]{\text{true}}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/df8ace6756e8eb61912319cac249410fd2593646)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}p\land q\\[4pt]p=q\\[4pt]q\\[4pt]p\Rightarrow q\\[4pt]p\\[4pt]p\Leftarrow q\\[4pt]p\lor q\\[4pt]1\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8815f64997b0bbaeaa461fd82740818443f4a257)

|

The next four Tables expand the expressions of  and

and  in two different ways, for each of the sixteen functions. Notice that the functions are given in a different order, partitioned into seven natural classes by a group action.

in two different ways, for each of the sixteen functions. Notice that the functions are given in a different order, partitioned into seven natural classes by a group action.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{1}\\[4pt]f_{2}\\[4pt]f_{4}\\[4pt]f_{8}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5fba44afb961cb2dbaf2240e33d357dad15f121)

|

~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81748741e62c1db5e26b5939f1bc0797ffa351b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~p~~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt](p)~q~\\[4pt](p)(q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9788a6826581fdf18bd2c8b88bbb9f092ad0bb5d)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\\[4pt](p)(q)\\[4pt](p)~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2c93b61569143a7d7f7bef1028182d85c2b436d5)

|

(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1d378fd45fee3ce34468a76fd6f3ba85dd7f22c8)

|

~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81748741e62c1db5e26b5939f1bc0797ffa351b4)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{3}\\[4pt]f_{12}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aa6290e9adb92ebd0bf4bbb2b24e945e854b8e64)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e47cd1c867059a78f9a82b591f7d45e4a733fba6)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e47cd1c867059a78f9a82b591f7d45e4a733fba6)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{6}\\[4pt]f_{9}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4cb2a3bf7befe00d4b81aee3fc461d99b4ea3439)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((p,~q))\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3e959e929cccb2ce9fe593cb3bfe57512756f316)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((p,~q))\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3e959e929cccb2ce9fe593cb3bfe57512756f316)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{5}\\[4pt]f_{10}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/36193deb2abdf99110489300c384c860e3017501)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d173b80cbd38d6a8f526e157a1b293f42dbbfa65)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d173b80cbd38d6a8f526e157a1b293f42dbbfa65)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{7}\\[4pt]f_{11}\\[4pt]f_{13}\\[4pt]f_{14}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e7410c0beab36a0effc596cb83a2da0e538412b7)

|

)\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\\[4pt]((p)(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/64781395ef829df6fdae2846612720cec8d27ea9)

|

~q~)\\[4pt](~p~(q))\\[4pt](~p~~q~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f9e77f8097405ef2e4bd94494c4038ae46aab401)

|

(q))\\[4pt](~p~~q~)\\[4pt](~p~(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8ce81b77ca39e83944db42f6ed0dc89700b4133a)

|

\\[4pt]((p)(q))\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fdcb5e5c4a1b88747d90f62ed399c5869a89bd8a)

|

)\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\\[4pt]((p)(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/64781395ef829df6fdae2846612720cec8d27ea9)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{1}\\[4pt]f_{2}\\[4pt]f_{4}\\[4pt]f_{8}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5fba44afb961cb2dbaf2240e33d357dad15f121)

|

~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81748741e62c1db5e26b5939f1bc0797ffa351b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((p,~q))\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\\[4pt]((p,~q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/11819900953aa5d449163d4a84e62c85b0d6905c)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\\[4pt](q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6addcde0d4b7e2132c70401b7be90a974a345430)

|

\\[4pt]~p~\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2011faa1bc2dc8da34679cd8ed03842f8b996050)

|

\\[4pt](~)\\[4pt](~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6447fbbe3f1bc7664adb58c4fe5229360ad64b9d)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{3}\\[4pt]f_{12}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aa6290e9adb92ebd0bf4bbb2b24e945e854b8e64)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90e990f7a6b9d7c53311974e3ba529e0b9b70aed)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90e990f7a6b9d7c53311974e3ba529e0b9b70aed)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f3845559254e88a63b03698d613b681da5c93414)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f3845559254e88a63b03698d613b681da5c93414)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{6}\\[4pt]f_{9}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4cb2a3bf7befe00d4b81aee3fc461d99b4ea3439)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f3845559254e88a63b03698d613b681da5c93414)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90e990f7a6b9d7c53311974e3ba529e0b9b70aed)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90e990f7a6b9d7c53311974e3ba529e0b9b70aed)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f3845559254e88a63b03698d613b681da5c93414)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{5}\\[4pt]f_{10}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/36193deb2abdf99110489300c384c860e3017501)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90e990f7a6b9d7c53311974e3ba529e0b9b70aed)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f3845559254e88a63b03698d613b681da5c93414)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/90e990f7a6b9d7c53311974e3ba529e0b9b70aed)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f3845559254e88a63b03698d613b681da5c93414)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{7}\\[4pt]f_{11}\\[4pt]f_{13}\\[4pt]f_{14}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e7410c0beab36a0effc596cb83a2da0e538412b7)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~(p~~q)~\\[4pt]~(p~(q))\\[4pt]((p)~q)~\\[4pt]((p)(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b33e381581cb5f1a0cc01245edf9f3515714c745)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((p,~q))\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\\[4pt]((p,~q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/11819900953aa5d449163d4a84e62c85b0d6905c)

|

\\[4pt]~q~\\[4pt](q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3e705c40c4d7c668b19881797a44845e48e3a646)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~p~\\[4pt]~p~\\[4pt](p)\\[4pt](p)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/558469860a22e08ffde33963c29b7298004d67f2)

|

\\[4pt](~)\\[4pt](~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6447fbbe3f1bc7664adb58c4fe5229360ad64b9d)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{1}\\[4pt]f_{2}\\[4pt]f_{4}\\[4pt]f_{8}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5fba44afb961cb2dbaf2240e33d357dad15f121)

|

~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81748741e62c1db5e26b5939f1bc0797ffa351b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt](\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~\\[4pt](\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/41d06c4f4256e788d7aabeab4caec66967e337b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~\\[4pt](\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt](\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/805a6e4034c30ba94c84648e8166643ce1f56ec3)

|

(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8cd2f516ddcde8da259ffcd60f189f17e8f62e11)

|

~\mathrm {d} q~\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ad9aea744a9dc8fa0d822a37b874f72a6088033)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{3}\\[4pt]f_{12}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aa6290e9adb92ebd0bf4bbb2b24e945e854b8e64)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/20d39eb3294aefbb31746fb69efecfb8da999c8b)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/20d39eb3294aefbb31746fb69efecfb8da999c8b)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(\mathrm {d} p)\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5b99ea186c87507024a972b85c72e636644457c)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(\mathrm {d} p)\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5b99ea186c87507024a972b85c72e636644457c)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{6}\\[4pt]f_{9}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4cb2a3bf7befe00d4b81aee3fc461d99b4ea3439)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f99b074b547d0d72db336a3a6ca9589f40a1770)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((\mathrm {d} p,~\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p,~\mathrm {d} q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b4b414b49c9dce6c2dcdf427d4a1084ae104ab8e)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((\mathrm {d} p,~\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p,~\mathrm {d} q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b4b414b49c9dce6c2dcdf427d4a1084ae104ab8e)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f99b074b547d0d72db336a3a6ca9589f40a1770)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{5}\\[4pt]f_{10}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/36193deb2abdf99110489300c384c860e3017501)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d34066bfe49c2d8c1fa2fe25149c8dead0b62ab4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3cb4b4bf993f9160123a8d124b50310e78c0d101)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d34066bfe49c2d8c1fa2fe25149c8dead0b62ab4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(\mathrm {d} q)\\[4pt]~\mathrm {d} q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3cb4b4bf993f9160123a8d124b50310e78c0d101)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{7}\\[4pt]f_{11}\\[4pt]f_{13}\\[4pt]f_{14}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e7410c0beab36a0effc596cb83a2da0e538412b7)

|

)\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\\[4pt]((p)(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/64781395ef829df6fdae2846612720cec8d27ea9)

|

~\mathrm {d} q~)\\[4pt](~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt](~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/25fd93f0ce3b6f220d4243a4a2d663753f36a7cb)

|

(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt](~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~)\\[4pt](~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6e47ea887586eccb1e39572ae75c04238fa805c2)

|

\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f6a0ab0bd24935b7ddbe1af86af40be893dda4a6)

|

)\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~)\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ed37af8d57286a4e269448db9f160ef265b1724a)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{1}\\[4pt]f_{2}\\[4pt]f_{4}\\[4pt]f_{8}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5fba44afb961cb2dbaf2240e33d357dad15f121)

|

~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81748741e62c1db5e26b5939f1bc0797ffa351b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f78262117da96311f481b0599bfb8013d413f295)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/83f37b7ec2cb4a36ef98f3a9da056d5b1e1fe984)

|

(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f46bb1172718af59ca8aa4dcd0803d006f076339)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7002523baf6310c776d6c69c1859a60f961fae37)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{3}\\[4pt]f_{12}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aa6290e9adb92ebd0bf4bbb2b24e945e854b8e64)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} p\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} p\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/974baebcc95b572f5dd9110995eb2a3c30c011b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} p\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} p\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/974baebcc95b572f5dd9110995eb2a3c30c011b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} p\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} p\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/974baebcc95b572f5dd9110995eb2a3c30c011b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} p\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} p\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/974baebcc95b572f5dd9110995eb2a3c30c011b4)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{6}\\[4pt]f_{9}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4cb2a3bf7befe00d4b81aee3fc461d99b4ea3439)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fedc9eef825e4a87e2f15850c1b74d48c78ad742)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fedc9eef825e4a87e2f15850c1b74d48c78ad742)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fedc9eef825e4a87e2f15850c1b74d48c78ad742)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fedc9eef825e4a87e2f15850c1b74d48c78ad742)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{5}\\[4pt]f_{10}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/36193deb2abdf99110489300c384c860e3017501)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} q\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} q\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/045dd0eca6bb842f173c36ffe7771bfab6e933f0)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} q\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} q\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/045dd0eca6bb842f173c36ffe7771bfab6e933f0)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} q\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} q\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/045dd0eca6bb842f173c36ffe7771bfab6e933f0)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {d} q\\[4pt]\mathrm {d} q\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/045dd0eca6bb842f173c36ffe7771bfab6e933f0)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{7}\\[4pt]f_{11}\\[4pt]f_{13}\\[4pt]f_{14}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e7410c0beab36a0effc596cb83a2da0e538412b7)

|

)\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\\[4pt]((p)(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/64781395ef829df6fdae2846612720cec8d27ea9)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7002523baf6310c776d6c69c1859a60f961fae37)

|

(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f46bb1172718af59ca8aa4dcd0803d006f076339)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/83f37b7ec2cb4a36ef98f3a9da056d5b1e1fe984)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~~\mathrm {d} p~~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]~~\mathrm {d} p~(\mathrm {d} q)~\\[4pt]~(\mathrm {d} p)~\mathrm {d} q~~\\[4pt]((\mathrm {d} p)(\mathrm {d} q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f78262117da96311f481b0599bfb8013d413f295)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Operational Representation

edit

If you think that I linger in the realm of logical difference calculus out of sheer vacillation about getting down to the differential proper, it is probably out of a prior expectation that you derive from the art or the long-engrained practice of real analysis. But the fact is that ordinary calculus only rushes on to the sundry orders of approximation because the strain of comprehending the full import of  and

and  at once overwhelms its discrete and finite powers to grasp them. But here, in the fully serene idylls of zeroth order logic, we find ourselves fit with the compass of a wit that is all we'd ever need to explore their effects with care.

at once overwhelms its discrete and finite powers to grasp them. But here, in the fully serene idylls of zeroth order logic, we find ourselves fit with the compass of a wit that is all we'd ever need to explore their effects with care.

So let us do just that.

I will first rationalize the novel grouping of propositional forms in the last set of Tables, as that will extend a gentle invitation to the mathematical subject of group theory, and demonstrate its relevance to differential logic in a strikingly apt and useful way. The data for that account is contained in Table A3.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{1}\\[4pt]f_{2}\\[4pt]f_{4}\\[4pt]f_{8}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b5fba44afb961cb2dbaf2240e33d357dad15f121)

|

~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81748741e62c1db5e26b5939f1bc0797ffa351b4)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~p~~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt](p)~q~\\[4pt](p)(q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9788a6826581fdf18bd2c8b88bbb9f092ad0bb5d)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\\[4pt](p)(q)\\[4pt](p)~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2c93b61569143a7d7f7bef1028182d85c2b436d5)

|

(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1d378fd45fee3ce34468a76fd6f3ba85dd7f22c8)

|

~q~\\[4pt]~p~(q)\\[4pt]~p~~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81748741e62c1db5e26b5939f1bc0797ffa351b4)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{3}\\[4pt]f_{12}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aa6290e9adb92ebd0bf4bbb2b24e945e854b8e64)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e47cd1c867059a78f9a82b591f7d45e4a733fba6)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e47cd1c867059a78f9a82b591f7d45e4a733fba6)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(p)\\[4pt]~p~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e08693cc41bcd7d3657d2213a4efd47e3131654)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{6}\\[4pt]f_{9}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4cb2a3bf7befe00d4b81aee3fc461d99b4ea3439)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((p,~q))\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3e959e929cccb2ce9fe593cb3bfe57512756f316)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}((p,~q))\\[4pt]~(p,~q)~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3e959e929cccb2ce9fe593cb3bfe57512756f316)

|

)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0aa3fed3d6d9afbc48711965de1073303f229c69)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{5}\\[4pt]f_{10}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/36193deb2abdf99110489300c384c860e3017501)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d173b80cbd38d6a8f526e157a1b293f42dbbfa65)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d173b80cbd38d6a8f526e157a1b293f42dbbfa65)

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}(q)\\[4pt]~q~\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88fa770ccca77b5373b42740b5d8cd533d950230)

|

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}f_{7}\\[4pt]f_{11}\\[4pt]f_{13}\\[4pt]f_{14}\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e7410c0beab36a0effc596cb83a2da0e538412b7)

|

)\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\\[4pt]((p)(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/64781395ef829df6fdae2846612720cec8d27ea9)

|

~q~)\\[4pt](~p~(q))\\[4pt](~p~~q~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f9e77f8097405ef2e4bd94494c4038ae46aab401)

|

(q))\\[4pt](~p~~q~)\\[4pt](~p~(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8ce81b77ca39e83944db42f6ed0dc89700b4133a)

|

\\[4pt]((p)(q))\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fdcb5e5c4a1b88747d90f62ed399c5869a89bd8a)

|

)\\[4pt]((p)~q~)\\[4pt]((p)(q))\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/64781395ef829df6fdae2846612720cec8d27ea9)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The shift operator  can be understood as enacting a substitution operation on the propositional form

can be understood as enacting a substitution operation on the propositional form  that is given as its argument. In our present focus on propositional forms that involve two variables, we have the following type specifications and definitions:

that is given as its argument. In our present focus on propositional forms that involve two variables, we have the following type specifications and definitions:

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{lcl}\mathrm {E} ~:~(X\to \mathbb {B} )&\to &(\mathrm {E} X\to \mathbb {B} )\\[6pt]\mathrm {E} ~:~f(p,q)&\mapsto &\mathrm {E} f(p,q,\mathrm {d} p,\mathrm {d} q)\\[6pt]\mathrm {E} f(p,q,\mathrm {d} p,\mathrm {d} q)&=&f(p+\mathrm {d} p,q+\mathrm {d} q)\\[6pt]&=&f({\texttt {(}}p,\mathrm {d} p{\texttt {)}},{\texttt {(}}q,\mathrm {d} q{\texttt {)}})\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/24a0723cffe97f94182fc260be95a48566cd5c76)

|

Evaluating  at particular values of

at particular values of  and

and  for example,

for example,  and

and  where

where  and

and  are values in

are values in  produces the following result:

produces the following result:

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{lclcl}\mathrm {E} _{ij}&:&(X\to \mathbb {B} )&\to &(X\to \mathbb {B} )\\[6pt]\mathrm {E} _{ij}&:&f&\mapsto &\mathrm {E} _{ij}f\\[6pt]\mathrm {E} _{ij}f&=&\mathrm {E} f|_{\mathrm {d} p=i,\mathrm {d} q=j}&=&f(p+i,q+j)\\[6pt]&&&=&f({\texttt {(}}p,i{\texttt {)}},{\texttt {(}}q,j{\texttt {)}})\end{array}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a1d88a1863c7d85eafab594416d13613b32f2eb7)

|

The notation is a little awkward, but the data of Table A3 should make the sense clear. The important thing to observe is that  has the effect of transforming each proposition

has the effect of transforming each proposition  into a proposition

into a proposition  As it happens, the action of each

As it happens, the action of each  is one-to-one and onto, so the gang of four operators

is one-to-one and onto, so the gang of four operators  is an example of what is called a transformation group on the set of sixteen propositions. Bowing to a longstanding local and linear tradition, I will therefore redub the four elements of this group as

is an example of what is called a transformation group on the set of sixteen propositions. Bowing to a longstanding local and linear tradition, I will therefore redub the four elements of this group as  to bear in mind their transformative character, or nature, as the case may be. Abstractly viewed, this group of order four has the following operation table:

to bear in mind their transformative character, or nature, as the case may be. Abstractly viewed, this group of order four has the following operation table:

It happens that there are just two possible groups of 4 elements. One is the cyclic group  (from German Zyklus), which this is not. The other is the Klein four-group

(from German Zyklus), which this is not. The other is the Klein four-group  (from German Vier), which this is.

(from German Vier), which this is.

More concretely viewed, the group as a whole pushes the set of sixteen propositions around in such a way that they fall into seven natural classes, called orbits. One says that the orbits are preserved by the action of the group. There is an Orbit Lemma of immense utility to “those who count” which, depending on your upbringing, you may associate with the names of Burnside, Cauchy, Frobenius, or some subset or superset of these three, vouching that the number of orbits is equal to the mean number of fixed points, in other words, the total number of points (in our case, propositions) that are left unmoved by the separate operations, divided by the order of the group. In this instance,  operates as the group identity, fixing all 16 propositions, while the other three group elements fix 4 propositions each, and so we get: Number of Orbits = (4 + 4 + 4 + 16) ÷ 4 = 7. Amazing!

operates as the group identity, fixing all 16 propositions, while the other three group elements fix 4 propositions each, and so we get: Number of Orbits = (4 + 4 + 4 + 16) ÷ 4 = 7. Amazing!

|

Consider what effects that might conceivably have practical bearings you conceive the objects of your conception to have. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object.

|

| — Charles Sanders Peirce, “Issues of Pragmaticism”, (CP 5.438)

|

One other subject that it would be opportune to mention at this point, while we have an object example of a mathematical group fresh in mind, is the relationship between the pragmatic maxim and what are commonly known in mathematics as representation principles. As it turns out, with regard to its formal characteristics, the pragmatic maxim unites the aspects of a representation principle with the attributes of what would ordinarily be known as a closure principle. We will consider the form of closure that is invoked by the pragmatic maxim on another occasion, focusing here and now on the topic of group representations.

Let us return to the example of the four-group  We encountered this group in one of its concrete representations, namely, as a transformation group that acts on a set of objects, in this case a set of sixteen functions or propositions. Forgetting about the set of objects that the group transforms among themselves, we may take the abstract view of the group's operational structure, for example, in the form of the group operation table copied here:

We encountered this group in one of its concrete representations, namely, as a transformation group that acts on a set of objects, in this case a set of sixteen functions or propositions. Forgetting about the set of objects that the group transforms among themselves, we may take the abstract view of the group's operational structure, for example, in the form of the group operation table copied here:

This table is abstractly the same as, or isomorphic to, the versions with the  operators and the

operators and the  transformations that we took up earlier. That is to say, the story is the same, only the names have been changed. An abstract group can have a variety of significantly and superficially different representations. But even after we have long forgotten the details of any particular representation there is a type of concrete representations, called regular representations, that are always readily available, as they can be generated from the mere data of the abstract operation table itself.

transformations that we took up earlier. That is to say, the story is the same, only the names have been changed. An abstract group can have a variety of significantly and superficially different representations. But even after we have long forgotten the details of any particular representation there is a type of concrete representations, called regular representations, that are always readily available, as they can be generated from the mere data of the abstract operation table itself.

To see how a regular representation is constructed from the abstract operation table, select a group element from the top margin of the Table, and “consider its effects” on each of the group elements as they are listed along the left margin. We may record these effects as Peirce usually did, as a logical aggregate of elementary dyadic relatives, that is, as a logical disjunction or boolean sum whose terms represent the ordered pairs of  transactions that are produced by each group element in turn. This forms one of the two possible regular representations of the group, in this case the one that is called the post-regular representation or the right regular representation. It has long been conventional to organize the terms of this logical aggregate in the form of a matrix:

transactions that are produced by each group element in turn. This forms one of the two possible regular representations of the group, in this case the one that is called the post-regular representation or the right regular representation. It has long been conventional to organize the terms of this logical aggregate in the form of a matrix:

Reading “ ” as a logical disjunction:

” as a logical disjunction:

|

|

And so, by expanding effects, we get:

|

![{\displaystyle {\begin{matrix}\mathrm {G} &=&\mathrm {e} :\mathrm {e} &+&\mathrm {f} :\mathrm {f} &+&\mathrm {g} :\mathrm {g} &+&\mathrm {h} :\mathrm {h} \\[4pt]&+&\mathrm {e} :\mathrm {f} &+&\mathrm {f} :\mathrm {e} &+&\mathrm {g} :\mathrm {h} &+&\mathrm {h} :\mathrm {g} \\[4pt]&+&\mathrm {e} :\mathrm {g} &+&\mathrm {f} :\mathrm {h} &+&\mathrm {g} :\mathrm {e} &+&\mathrm {h} :\mathrm {f} \\[4pt]&+&\mathrm {e} :\mathrm {h} &+&\mathrm {f} :\mathrm {g} &+&\mathrm {g} :\mathrm {f} &+&\mathrm {h} :\mathrm {e} \end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d580462f517c67ead6241f6121bf91d01332b0d2)

|

More on the pragmatic maxim as a representation principle later.

The above-mentioned fact about the regular representations of a group is universally known as Cayley's Theorem, typically stated in the following form:

Every group is isomorphic to a subgroup of  the group of automorphisms of a suitably chosen set the group of automorphisms of a suitably chosen set  . .

|

There is a considerable generalization of these regular representations to a broad class of relational algebraic systems in Peirce's earliest papers. The crux of the whole idea is this:

| Contemplate the effects of the symbol whose meaning you wish to investigate as they play out on all the stages of conduct where you can imagine that symbol playing a role.

|

This idea of contextual definition by way of conduct transforming operators is basically the same as Jeremy Bentham's notion of paraphrasis, a “method of accounting for fictions by explaining various purported terms away” (Quine, in Van Heijenoort, From Frege to Gödel, p. 216). Today we'd call these constructions term models. This, again, is the big idea behind Schönfinkel's combinators  and hence of lambda calculus, and I reckon you know where that leads.

and hence of lambda calculus, and I reckon you know where that leads.

The next few excursions in this series will provide a scenic tour of various ideas in group theory that will turn out to be of constant guidance in several of the settings that are associated with our topic.

Let me return to Peirce's early papers on the algebra of relatives to pick up the conventions that he used there, and then rewrite my account of regular representations in a way that conforms to those.

Peirce describes the action of an “elementary dual relative” in this way:

Elementary simple relatives are connected together in systems of four. For if  be taken to denote the elementary relative which multiplied into be taken to denote the elementary relative which multiplied into  gives gives  then this relation existing as elementary, we have the four elementary relatives then this relation existing as elementary, we have the four elementary relatives

|

|

| C.S. Peirce, Collected Papers, CP 3.123.

|

Peirce is well aware that it is not at all necessary to arrange the elementary relatives of a relation into arrays, matrices, or tables, but when he does so he tends to prefer organizing 2-adic relations in the following manner:

|

|

For example, given the set  suppose that we have the 2-adic relative term

suppose that we have the 2-adic relative term  and the associated 2-adic relation

and the associated 2-adic relation  the general pattern of whose common structure is represented by the following matrix:

the general pattern of whose common structure is represented by the following matrix:

|

|

For at least a little while longer, I will keep explicit the distinction between a relative term like  and a relation like

and a relation like  but it is best to view both these entities as involving different applications of the same information, and so we could just as easily write the following form:

but it is best to view both these entities as involving different applications of the same information, and so we could just as easily write the following form:

|

|

By way of making up a concrete example, let us say that  or

or  is given as follows:

is given as follows:

|

|

In sum, then, the relative term  and the relation

and the relation  are both represented by the following matrix:

are both represented by the following matrix:

|

|

I think this much will serve to fix notation and set up the remainder of the discussion.

In Peirce's time, and even in some circles of mathematics today, the information indicated by the elementary relatives  as the indices

as the indices  range over the universe of discourse, would be referred to as the umbral elements of the algebraic operation represented by the matrix, though I seem to recall that Peirce preferred to call these terms the “ingredients”. When this ordered basis is understood well enough, one will tend to drop any mention of it from the matrix itself, leaving us nothing but these bare bones:

range over the universe of discourse, would be referred to as the umbral elements of the algebraic operation represented by the matrix, though I seem to recall that Peirce preferred to call these terms the “ingredients”. When this ordered basis is understood well enough, one will tend to drop any mention of it from the matrix itself, leaving us nothing but these bare bones:

|

|

The various representations of  are nothing more than alternative ways of specifying its basic ingredients, namely, the following aggregate of elementary relatives:

are nothing more than alternative ways of specifying its basic ingredients, namely, the following aggregate of elementary relatives:

|

|

Recognizing that  is the identity transformation otherwise known as

is the identity transformation otherwise known as  the 2-adic relative term

the 2-adic relative term  can be parsed as an element

can be parsed as an element  of the so-called group ring, all of which makes this element just a special sort of linear transformation.

of the so-called group ring, all of which makes this element just a special sort of linear transformation.

Up to this point, we are still reading the elementary relatives of the form  in the way that Peirce read them in logical contexts:

in the way that Peirce read them in logical contexts:  is the relate,

is the relate,  is the correlate, and in our current example

is the correlate, and in our current example  or more exactly,

or more exactly,  is taken to say that

is taken to say that  is a marker for

is a marker for  This is the mode of reading that we call “multiplying on the left”.

This is the mode of reading that we call “multiplying on the left”.

In the algebraic, permutational, or transformational contexts of application, however, Peirce converts to the alternative mode of reading, although still calling  the relate and

the relate and  the correlate, the elementary relative

the correlate, the elementary relative  now means that

now means that  gets changed into

gets changed into  In this scheme of reading, the transformation

In this scheme of reading, the transformation  is a permutation of the aggregate

is a permutation of the aggregate  or what we would now call the set

or what we would now call the set  in particular, it is the permutation that is otherwise notated as follows:

in particular, it is the permutation that is otherwise notated as follows:

|

|

This is consistent with the convention that Peirce uses in the paper “On a Class of Multiple Algebras” (CP 3.324–327).

We've been exploring the applications of a certain technique for clarifying abstruse concepts, a rough-cut version of the pragmatic maxim that I've been accustomed to refer to as the operationalization of ideas. The basic idea is to replace the question of What it is, which modest people comprehend is far beyond their powers to answer definitively any time soon, with the question of What it does, which most people know at least a modicum about.

In the case of regular representations of groups we found a non-plussing surplus of answers to sort our way through. So let us track back one more time to see if we can learn any lessons that might carry over to more realistic cases.

Here is is the operation table of  once again:

once again:

A group operation table is really just a device for recording a certain 3-adic relation, to be specific, the set of triples of the form  satisfying the equation

satisfying the equation

In the case of  where

where  is the underlying set

is the underlying set  we have the 3-adic relation

we have the 3-adic relation  whose triples are listed below:

whose triples are listed below:

|

&(\mathrm {f} ,\mathrm {f} ,\mathrm {e} )&(\mathrm {f} ,\mathrm {g} ,\mathrm {h} )&(\mathrm {f} ,\mathrm {h} ,\mathrm {g} )\\[6pt](\mathrm {g} ,\mathrm {e} ,\mathrm {g} )&(\mathrm {g} ,\mathrm {f} ,\mathrm {h} )&(\mathrm {g} ,\mathrm {g} ,\mathrm {e} )&(\mathrm {g} ,\mathrm {h} ,\mathrm {f} )\\[6pt](\mathrm {h} ,\mathrm {e} ,\mathrm {h} )&(\mathrm {h} ,\mathrm {f} ,\mathrm {g} )&(\mathrm {h} ,\mathrm {g} ,\mathrm {f} )&(\mathrm {h} ,\mathrm {h} ,\mathrm {e} )\end{matrix}}\!~}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1b993835968188b5a5525ee2cf4ee033fa6e0701)

|

It is part of the definition of a group that the 3-adic relation  is actually a function

is actually a function  It is from this functional perspective that we can see an easy way to derive the two regular representations. Since we have a function of the type

It is from this functional perspective that we can see an easy way to derive the two regular representations. Since we have a function of the type  we can define a couple of substitution operators:

we can define a couple of substitution operators:

| 1.

|

puts any specified puts any specified  into the empty slot of the rheme into the empty slot of the rheme  with the effect of producing the saturated rheme with the effect of producing the saturated rheme  that evaluates to that evaluates to

|

| 2.

|

puts any specified puts any specified  into the empty slot of the rheme into the empty slot of the rheme  with the effect of producing the saturated rheme with the effect of producing the saturated rheme  that evaluates to that evaluates to

|

In (1) we consider the effects of each  in its practical bearing on contexts of the form

in its practical bearing on contexts of the form  as

as  ranges over

ranges over  and the effects are such that

and the effects are such that  takes

takes  into

into  for

for  in

in  all of which is notated as

all of which is notated as  The pairs