Bully Metric Bohr Model

The following text was copied from the Wikipedia Bohr model article and was adapted to use Bully Metric Units:

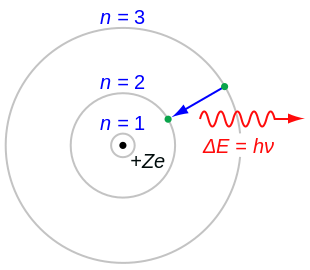

In atomic physics, the Bohr model or Rutherford–Bohr model was the first successful model of the atom (see Figure 1). Developed from 1911 to 1918 by Niels Bohr and building on Ernest Rutherford's nuclear model. It supplanted the plum pudding model of J J Thomson only to be replaced by the quantum atomic model in the 1920s. It consists of a small, dense nucleus surrounded by orbiting electrons. It is analogous to the structure of the Solar System, but with attraction provided by electrostatic force rather than gravity, and with the electron energies quantized (assuming only discrete values).

Development

editIn 1913 Niels Bohr put forth three postulates to provide an electron model consistent with Rutherford's nuclear model:

- The electron is able to revolve in certain stable orbits around the nucleus without radiating any energy, contrary to what classical electromagnetism suggests. These stable orbits are called stationary orbits and are attained at certain discrete distances from the nucleus. The electron cannot have any other orbit in between the discrete ones.

- The stationary orbits are attained at distances for which the angular momentum of the revolving electron is an integer multiple of the reduced Planck constant: , where is called the principal quantum number, and . The lowest value of is 1; this gives the smallest possible orbital radius, known as the Bohr radius, of 5.777 889 micropan (52.917 721 picometers) for hydrogen. Once an electron is in this lowest orbit, it can get no closer to the nucleus.

- Electrons can only gain and lose energy by jumping from one allowed orbit to another, absorbing or emitting electromagnetic radiation with a frequency determined by the energy difference of the levels according to the Planck relation: , where is the Planck constant.

Calculation of the orbits

editCalculation of the orbits requires two assumptions, classical electromagnetism and a quantum rule.

- classical electromagnetism

- The electron is held in a circular orbit by electrostatic attraction. The centripetal force is therefore equal to the Coulomb force.

- where me is the electron's mass, e is the elementary charge, ke is the Coulomb constant and Z is the atom's atomic number. This classical equation determines that the product of the orbital radius (r) with the square of the electron's momentum (p = me v), is constant for a given atomic number (Z):

- It will be advantageous to represent the Coulomb constant ke in terms of the Reduced Planck constant ħ, the speed of light c, the elementary charge e, and the fine-structure constant α.

- From whence Bohr's classical electromagnetism equation becomes:

- a quantum rule

- The magnitude of angular momentum is an integer (n) multiple of ħ:

- For a circular orbit, the electron's total momentum (p) will always be perpendicular to the orbital radius (r), thus:

- model assumptions

- Bohr's model assumes that the mass of the nucleus is much larger than the electron mass, allowing the nucleus to sit mostly stationary while the electron orbits around it. This can be explicitly stated as:

- where me is the electron's mass, Z is the number of protons, N is the number of neutrons, and u is the unified atomic mass unit.

- The relativistic corrections necessary for a system where two charged points orbit each other at speeds approaching that of light are not included in Bohr's model. The model assumes that the electron velocity is significantly less than that of light:

- where me is the electron's mass and c is the speed of light.

- in summary

Conversion to Bully Metric Units

editIn Bully Metric units, the speed of light (c = 1 la / ta), the reduced Planck constant (ħ = 1 An), and the elementary charge (1 e) are all normalized, which means that many of the electron's properties carry the same numeric value but with differing units as shown in Table 1.

| Electron Mass (m) | mc | mcħ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23717311.411 | An ta la-2 | 23717311.411 | An la-1 | 23717311.411 | An^2 la-1 |

Bohr's Quantization Rule in Bully Units

editThe quantization rule:

- can be written in Bully units as:

This rule is not a special property of the Bohr atom, but rather, is a universal property of quantum mechanics called quantization of angular momentum. This rule has an extremely simple form when momentum and radius are plotted on a log-log graph using Bully units (see Figure 2). The quantization of angular momentum appears as a series of parallel straight lines with a slope of negative one, each line representing an integer value of the principle quantum number n. The slope of negative one indicates that momentum in Bully units is proportional to the inverse of the radius.

Bohr's Classical Electromagnetism in Bully Units

editBohr's classical electromagnetism equation:

Can be written in Bully units as shown below (note that 137.035999177 is the inverse fine-structure constant and the value 23717311.411 is obtained from table 1 above):

For a hydrogen atom with one proton (Z = 1), this becomes:

When momentum and radius are plotted on a log-log graph using Bully units (see Figure 3), Bohr's classical electromagnetism equation appears as a straight line with a slope of negative two (negative two indicating that momentum squared is proportional to the inverse of the radius).

Bohr's Hydrogen Atom in Bully Units

editA solution (or energy level) of the Bohr model, is a point on the momentum-radius graph that satisfies both the classical electromagnetism equation and the quantization rule. Solutions of the Bohr model can be found algebraically through simple manipulation of Bohr's two equations:

From whence:

| n | Momentum | Radius |

|---|---|---|

| ∞ | 0.000 | ∞ |

| 1000 | 173.074 | 5.777889273 |

| 100 | 1730.736 | 0.057778893 |

| 10 | 17307.358 | 0.000577789 |

| 9 | 19230.398 | 0.000468009 |

| 8 | 21634.198 | 0.000369785 |

| 7 | 24724.798 | 0.000283117 |

| 6 | 28845.597 | 0.000208004 |

| 5 | 34614.717 | 0.000144447 |

| 4 | 43268.396 | 0.000092446 |

| 3 | 57691.194 | 0.000052001 |

| 2 | 86536.792 | 0.000023112 |

| 1 | 173073.583 | 0.000005778 |

Figure 3 illustrates and Table 1 lists Bohr model solutions for the hydrogen atom with principle quantum numbers one through ten (n = 1 .. 10), and for various powers of ten (n = 100, 1000, 10000, and 100000), and for infinity (solutions are marked with an asterisk(*) and labeled as "Energy Levels" in Figure 3).

Bohr Model Assumptions in Bully Units

editNote that for the hydrogen atom (Z = 1, N = 0), the electron/nucleon mass ratio assumption is satisfied, and the situation improves with an increased number of nucleons.

Note from Table 1 that the relativistic assumption is satisfied when n=1, and improves as n increases.

Universal Constants

editA trio of related constants are illustrated in Figure 3. These include the Bohr radius ( ), the reduced Compton wavelength ( ), and the classical electron radius ( ). Any one of these constants can be written in terms of any of the others using the fine-structure constant :

The Bohr radius of 5.777 889 micropan (52.917 721 picometers) is the smallest possible orbit for an electron in the Bohr hydrogen atom. Once an electron is in this lowest orbit, it can get no closer to the nucleus without violating one of Bohr's criteria.

However, if one were to imagine a counterfactual universe where the electron is subject to Bohr's quantization rule, but is not subject to the classical electromagnetism equation, then the electron's orbit might slide down closer to the nucleus, to the reduced Compton wavelength of 42.163 295 nanopan (386.15926744 femtometers) as shown in Figure 3. The reduced Compton wavelength is a solution of the following equations:

Or, if one were to imagine a counterfactual universe where the electron is subject Bohr's classical electromagnetism equation, but not subject to Bohr's quantization rule, then the electron's orbit might slide down even further to the classical electron radius of 307.680 picopan (2.8179403205 femtometers). The classical electron radius is a solution of the following equations:

Calculation of energy levels

editPotential energy (P) is the energy held by an object because of its position relative to other objects, stresses within itself, its electric charge, or other factors. In the Bohr model, the pertinent form of potential energy is electric potential . The kinetic energy (K) of an object is the form of energy that it possesses due to its motion. In classical mechanics, the kinetic energy of a non-rotating object of mass m traveling at a speed v is The total energy (E) of the Bohr model atom is:

- Note from previous sections that Bohr's classical electromagnetism equation requires:

- From whence:

- Thus:

The total energy here is negative and inversely proportional to r. This means that it takes energy to pull the orbiting electron away from the atom. For infinite values of r, the energy and momentum are both zero, corresponding to a motionless electron infinitely far from the proton. Table 3 lists the same solutions as Table 2 above, but Table 3 includes two additional columns for the energy and electron velocity of each solution.

| n | Velocity | Energy | Momentum | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∞ | 0.000000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ∞ |

| 1000 | 0.000007 | -0.001 | 173.074 | 5.777889273 |

| 100 | 0.000073 | -0.063 | 1730.736 | 0.057778893 |

| 10 | 0.000730 | -6.315 | 17307.358 | 0.000577789 |

| 9 | 0.000811 | -7.796 | 19230.398 | 0.000468009 |

| 8 | 0.000912 | -9.867 | 21634.198 | 0.000369785 |

| 7 | 0.001042 | -12.888 | 24724.798 | 0.000283117 |

| 6 | 0.001216 | -17.541 | 28845.597 | 0.000208004 |

| 5 | 0.001459 | -25.260 | 34614.717 | 0.000144447 |

| 4 | 0.001824 | -39.468 | 43268.396 | 0.000092446 |

| 3 | 0.002432 | -70.165 | 57691.194 | 0.000052001 |

| 2 | 0.003649 | -157.872 | 86536.792 | 0.000023112 |

| 1 | 0.007297 | -631.489 | 173073.583 | 0.000005778 |

Hydrogen spectral series

editThe following numeric values and some text were copied from the Wikipedia hydrogen spectral series article and adapted to use Bully Metric Units:

Table 4 provides a list of photons that are emitted or absorbed when an electron transitions to a different energy level within the Bohr hydrogen atom.

| Transition | Lyman series (n=1) |

Balmer series (n=2) |

Paschen series (n=3) |

Brackett series (n=4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n→∞ | 631.152904 631.489478 0.336574 |

157.875323 157.872370 -0.002954 |

70.143290 70.165498 0.022207 |

39.468831 39.468092 -0.000738 |

| n→9 | 623.360648 623.693312 0.332664 |

150.038067 150.076203 0.038136 |

62.346214 62.369331 0.023117 |

31.670641 31.671926 0.001285 |

| n→8 | 621.290915 621.622455 0.331540 |

147.967622 148.005346 0.037724 |

60.282375 60.298474 0.016099 |

29.601623 29.601069 -0.000554 |

| n→7 | 618.272041 618.601938 0.329896 |

144.948283 144.984829 0.036546 |

57.259259 57.277957 0.018698 |

26.567662 26.580552 0.012890 |

| n→6 | 613.620732 613.948104 0.327372 |

140.295678 140.330995 0.035317 |

52.601056 52.624123 0.023067 |

21.922116 21.926718 0.004602 |

| n→5 | 605.906685 606.229899 0.323214 |

132.579027 132.612790 0.033764 |

44.887329 44.905918 0.018590 |

14.205272 14.208513 0.003242 |

| n→4 | 591.705868 592.021386 0.315518 |

118.373611 118.404277 0.030666 |

30.690963 30.697405 0.006442 |

|

| n→3 | 561.024872 561.323981 0.299109 |

87.684591 87.706872 0.022281 |

||

| n→2 | 473.364899 473.617109 0.252210 |

- ↑ Lakhtakia, Akhlesh; Salpeter, Edwin E. (1996). "Models and Modelers of Hydrogen". American Journal of Physics 65 (9): 933. doi:10.1119/1.18691.