Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2021/Spring/105i/Section 22/Liza "Ma" Williams

Liza Williams | |

|---|---|

| Born | Georgia, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Unknown |

| Occupation |

|

| Children | 2 |

Overview

editLiza “Ma” Williams was an African American woman who was interviewed by the Federal Writers Project on January 13, 1939 in Savannah, Georgia.

Biography

editEarly Life

editAt the time of the interview Williams claimed to be born in 1836, making her 103 years old [1]. William was well known in her community as a root doctor, which is a "traditional healer and conjurer of the rural, black South."[2] Williams claims that she was born with the ability to heal, saying that it seemed like her abilities were present at birth.[3] In the Federal Writers Project Papers, she went on to say she just seemed to know how to make medicine and work cures[4]. When Williams was a child, she worked as a laundress at a variety of hotels.

Adult Life

editWilliams had a husband and two children. Her husband died of old age, and her daughter and son died from sudden illnesses. After no longer being able to work as a laundress due to her ailing health, she depended on her children for financial support.[5] Williams was religious throughout her adulthood, claiming in her interview with the Federal Writer's Project that witchcraft was created because of an interaction between God and Lucifer[6]. She was well known in her town for being a “root doctor,” or a traditional healer who uses spells, roots, and other ingredients. When neighbors were asked about Williams by Virginia Thorpe, the interviewer for the Federal Writer's Project, many individuals of the town believed she had special abilities in healing and harming. Those who claimed that they didn’t believe in Williams’ abilities still hesitated to say anything too severe against her.[7] In her old age she no longer healed people because she was previously brought to court for practicing witchcraft[8]. However, Williams still claimed to possess many recipes for certain concoctions and conjures[9]. In practicing witchcraft, Williams anointed the head of the individual with oil, wrapped their head, and said the words that are required for the healing[10]. At the height of Williams’ healing career, people were visiting her house at all hours of the night in need of healing[11]. As Williams aged, she stopped healing for the most part, but stayed true to her religious and spiritual beliefs.[12] Her date of death is unknown.[13]

Social Issues

editRoot Doctors

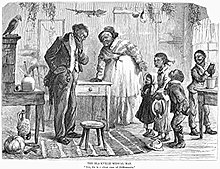

editRoot doctors came about during times of slavery and continued to be popular in African American culture even after slavery was abolished. Root doctors are defined as "the traditional healers and conjurers of the rural, black South. They use herbs, roots, potions, and spells to help and sometimes to hurt recipients of their ministrations."[14] An article titled "Root Doctor" by Troy D. Smith stated that “Slaves... took an active role in their own physical well-being. Doing so not only helped them stay healthy, it also gave them a measure of control over their lives."[15] African Americans had a difficult time seeing medical help because of the segregation and racism that was instilled in American society even after slavery was technically outlawed, so their next best option was to seek help from root doctors.[16] "Root Doctor" by Smith stated that “After emancipation, African Americans continued to utilize the services of root doctors and conjurers... Moreover, widespread racial hostility ensured that white doctors often provided inferior treatment to African American patients. Terrifying stories of physical abuse, experimentation, and mutilation circulated widely among African Americans, leading to a general mistrust of the white medical profession. In contrast, the services of root doctors and conjurers were relatively low cost, accessible, and trustworthy" [17].

Mass Imprisonment of African Americans

editSegregation and racial oppression were still common in America after slavery was abolished. An article titled "Systematic Inequality and American Democracy" by Danyelle Solomon, Connor Maxwell, and Abril Castro stated that "the death of Reconstruction fueled resurgence of white nationalist violence, occupational segregation, and racial discrimination designed to trap Black Americans in a semipermanent status of second-class citizenship."[18] Additionally, numerous efforts were put into effect in order to dismantle the Civil Rights movement and keep African Americans from having as much power as white individuals.[19] One way that the power of African Americans was limited was by accusing them of crimes such as witchcraft and practicing without a medical license. These laws put African American lives at risk of a prison sentence or execution, as these crimes were punishable by death.

Misconceptions Surrounding Witchcraft and the African American Community

editTituba, the first woman to be accused of practicing witchcraft during the Salem Witch Trials, has been depicted as an African American in the modern media, when it’s possible that she was actually Native American[20]. There are many confusions surrounding Tituba, many of which lead people to assume that witchcraft originated in Africa and African American culture. An article titled "Tracing Tituba through American Horror Story: Coven" by Dara Downey claims that “Tituba’s difference from the other women and men hanged at Salem, and her status as scapegoat for and catalyst to the 1692 trials, becomes a covert means of suggesting that witchcraft is never Anglo-European in origin, but can always be traced back to Africa and/or the New World.”[21] This depiction of Tituba "allows the intimations of devil worship and dark magic that remain inextricable from many depictions of witchcraft to be linked only to African Americans, often associated with abjectified religious beliefs and practices…”[22]. White people in specific used the misconceptions of being a root doctor as an excuse to take African Americans to court for witchcraft and kill other minorities for participating in such an activity [23].

Notes

edit- ↑ "Ma" Liza Williams, Federal Writers Project Papers

- ↑ Beck, John J. “Root Doctors.”

- ↑ "Ma" Liza Williams, Federal Writers Project Papers

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ "Ma" Liza Williams, Federal Writers Project Papers

- ↑ Beck, John J., "Root Doctors"

- ↑ Smith, Troy, "Root Doctor."

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Solomon, Maxwell, and Castro "Systematic Inequality and American Democracy"

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Downey, Dara "Tracing Tituba through American Horror Story: Coven"

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ ibid.

References

edit- DeLong, William. “Did This Slave Girl Provoke The Salem Witch Hunt To Win Her Own Freedom?” All That's Interesting. All That's Interesting, September 25, 2018. https://allthatsinteresting.com/tituba.

- “South Root Doctor NThe Blackville Medical Man.” Amazon, 2021. https://www.amazon.com/Blackville-Medical-Difflomania-Engraving-American/dp/B07CHZS4W6.

- Thorpe, Virginia. “Folder 253: Thorpe, Virginia (Interviewer): Root Doctor.” Federal Writers Project Papers. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/03709/id/700/rec/1.

- Smith, Troy. “." Gale Library of Daily Life: Slavery in America. . Encyclopedia.com. 8 Mar. 2021 .” Encyclopedia.com. Encyclopedia.com, March 8, 2021. https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/applied-and-social-sciences-magazines/root-doctors

- Danyelle Solomon, Connor Maxwell. “Systematic Inequality and American Democracy.” Center for American Progress, 2019. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2019/08/07/473003/systematic-inequality-american-democracy/.

- Downey, Dara, 2019 . “Tracing Tituba through American Horror Story: Coven.” European Journal of American Culture 38 (1): 15-27

- Beck, John J. “Root Doctors.” NCpedia, 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/root-doctors.