Federal Writers' Project – Life Histories/2018/Fall/Section 3/Kay James

Kay James was a manager of a hat shop who was interviewed in 1939 for the Federal Writers Project. [1]

Kay James | |

|---|---|

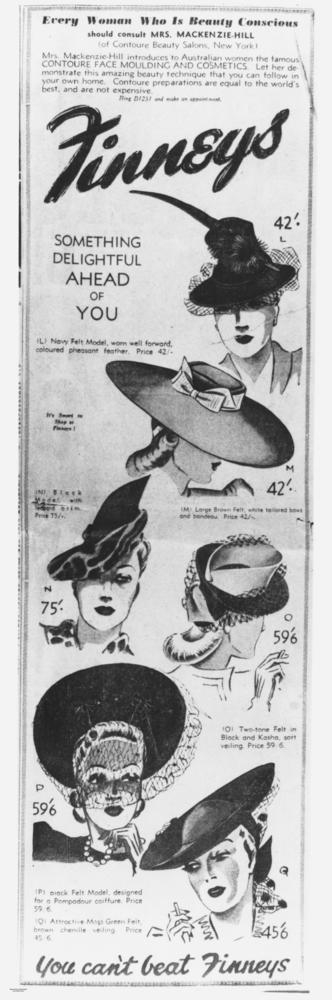

Advertisement for Women's Hats in the 1940's | |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | Unknown Unknown |

| Occupation | Saleswoman, Store Manager |

Biography

editEarly Life

editKay James was born on a cotton farm near Carrollton, Georgia to a middle-class family.[1] She had a brother and a sister. As a child, James helped out on her parents’ farm due to her father’s poor health.[1] As a child, James promised herself that she would leave the countryside and never come back. This happened when she was around the age of 13, and her family moved from rural Georgia to Cedartown, Georgia.[1] She attended high school in Rome, Georgia.[1] She was accepted to a co-educational boarding school named the Berry School. The Berry School was for academically successful children who could not afford to attend a traditional finishing school.[2] It was at this school that she met her future husband, who later became faculty. James specialized in millinery and dressmaking.

Career

editShe was married shortly after finishing school.[1] James and her family attended a Methodist church. She volunteered at a friend named Dorothy’s store in Chattanooga to gain experience. Eventually, she was offered a job at $10 a week. [1]After she went to work regularly in Chattanooga, her husband gave up his job and moved from Rome to be close to her.[1] His new job at a real estate company gave him $25 a week. James quit her job after three years, ending with a salary of $18 a week[1], which is worth approximately $260 a week in 2018 USD.[3] James stopped working when her daughter was born, but still took in sewing jobs for her old store.[1] Her husband was transferred to Athens, Georgia in 1928.[1] James applied to be the manager of a hat store that was being opened by a company from Atlanta, Georgia. Her application was accepted, and she took over management of the property. [1]It was in a lucrative location, which cost her $100 a month[1] (approx. 1,500 in 2018 USD)[3]. She sold inexpensive hats that ranged from $1 to $3, while making $15 a week. She was successful enough to hire a clerk for $10 a week.[1]

Social Issues

editWomen in the Workforce

editThe United States entered into the Great Depression in 1929. As a result, the unemployment rate of men increased to 25%.[4] Women and men, especially white middle-class families, had been conditioned with strong gender roles: men were providers and women were housewives.[5] However, when the Depression hit, these roles dramatically changed.

Many men lost their jobs and were unable to provide for their families. [6] Women, on the other hand, saw their roles increase and, in many cases, left the household and got a job to make ends meet. Up to one-third of the female workforce was married, which is a fifty-percent increase from the 1920s.[7] If women did not seek employment elsewhere, they used their own hands to make up for their family's decreased income. For example, they would mend and alter their old clothes instead of purchasing new ones.[8]

Hostility came from the women being hired outside of the homestead because the unemployment rate of men was equivalent to the employment rate of women. In the late 30's, the employment rate of women was 25.4%, and the unemployment rate of men was 25%. [9] This antagonistic attitude is reflected in a quote by Norman Cousins, “Simply fire the women, who shouldn’t be working anyway, and hire the men. Presto! No unemployment. No relief rolls. No depression.” This resulted in laws like the National Recovery Act being passed, which only allowed one family member to hold a government job, resulting in many women getting fired from the federal government.[10] Many programs from the New Deal like the Communications Workers of America, did not provide any jobs to women.

Women's Education

editWomen’s schools came about in the late 19th century, an era when according to Mildred H. McAfee, few Americans “really believed that women could stand the effects of higher education.” [11] Early women’s liberal arts colleges gave young women a chance to gain the same kinds of education as men without having to spend much of their time and energy fighting the prejudice they would have faced at male-dominated institutions. By the 1930's, 85% of baccalaureate programs were open for women to attend.[11] However, it was mostly elite white women who attended these institutions.[11]

Sex-segregated school systems, such as the Berry School, were intended to protect the virtue of female high school students[2]. Home economics and industrial education were taught in the high school curriculum designed for women's occupations or a life as a housewife. These classes taught women practical skills such as sewing and cooking. Unfortunately, the skills women were taught in schools were not practical in the many previously male-exclusive vocations that women inhabited in the Great Depression.[11]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 Hornsby, Hall, Booth: Kay's Shop, in the Federal Writers' Project papers #3709, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Berry College - About Martha Berry". www.berry.edu. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "US Inflation Calculator". US Inflation Calculator. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ↑ "Compare Today's Unemployment with the Past". The Balance. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ↑ Liker, Jeffrey K.; Elder, Glen H. (1983). "Economic Hardship and Marital Relations in the 1930s". American Sociological Review 48 (3): 343–359. doi:10.2307/2095227. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2095227.

- ↑ MacBride, Elizabeth (2013-09-26). "Suicide and the Economy". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ↑ Remy, Corry (2015-11-19). "Employment of Women in the 1930s". The Thirties. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ↑ Baillargeon, Denyse (1992-06). "‘If You Had No Money, You Had No Trouble, Did You?’: Montréal working‐class housewives during the Great Depression". Women's History Review 1 (2): 217–237. doi:10.1080/0961202920010202. ISSN 0961-2025. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/0961202920010202.

- ↑ Remy, Corry (2015-11-19). "Employment of Women in the 1930s". The Thirties. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ↑ "Detailed Timeline | National Women's History Alliance". www.nwhp.org. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Tidball, M. Elizabeth. “Women's Colleges and Women Achievers Revisited.” Signs, vol. 5, no. 3, 1980, pp. 504–517. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3173590.