Ascariasis

Ascariasis is a parasitic disease, among the so called Tropical Neglected Diseases, caused by the nematode Ascaris. It is one of the most common geohelminthiases which affects more than a billion people. Despite being spread around the world, the prevalence of this disease correlates with poor sanitary conditions, and it becomes endemic in many of the undeveloped countries.[1]

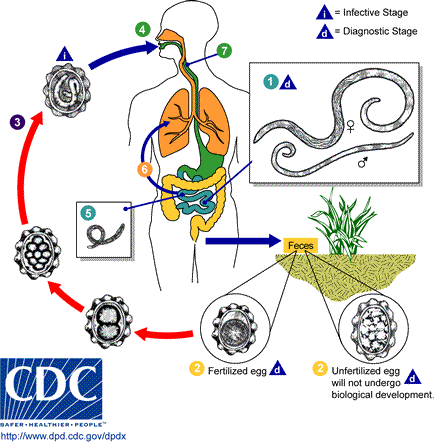

Infection occurs when embrionated eggs on contaminated food reach the human gastrointestinal tract. When this occurs, once inside the intestine, the larva inside the eggs hatches and migrates through the intestine wall to vein circulation. About three days later the larva reaches the lungs where it molts. After maturing, the L4 stage larva breaks the lung tissue and is swallowed by the patient when it arrives at the trachea. Finally the Ascaris larva approaches the small intestine where it molts to the adult state. A single female specimen can produce up to 200,000 eggs per day. These eggs are eliminated with feces that may contaminate soil to start the cycle over again.[2]

Symptoms

Clinical manifestations are generally associated with the obstruction these nematodes cause during migration or due to the large number of parasites residing in the intestine. Children, who are the most affected population, present malnutrition, growth impairment and low school performance.[3] Other symptoms are nonspecific and include abdominal pain, vomiting and anorexia, among others.

Treatment

The World Health Organization recommends the following drugs, which have been proved to be safe: albendazole, mebendazole, levamisole, and pyrantel pamoate. New drug targets are under research to deal with the eventual acquisition of drug resistance and in view of reduced efficacy of single dose drugs.[4]

Issues and solutions

Given that eggs contaminating the soil remain infective up to 15 years, controlling sanitary conditions and environmental improvement is high priority for achieving control in the dissemination of diseases caused by helminths. Repeated mass chemotherapy programs have also been successfully established in endemic areas with satisfactory results.[5] Furthermore in countries where sludge reuse for agricultural fertilization is a common practice emphasis should be placed on treatment of excreta that ensures helminth ova inactivation.[6] Finally regarding vaccination, despite there are no vaccines currently available for humans, there are ongoing trials that hold a lot of promise, for controlling parasitic infection in animals.[7]

References

- ↑ O’Lorcain, P.; Holland, C.V. The public health importance of Ascaris lumbricoides. Parasitology, 2000, 121(Suppl), S51-S71.

- ↑ http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/html/ascariasis.htm

- ↑ Hutchinson SE, Powell CA, Walker SP, Chang SM, Grantham-McGregor SM. Nutrition, anaemia, geohelminth infection and school achievement in rural Jamaican primary school children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997 Nov;51(11):729-35.

- ↑ Hagel I, Giusti T. Ascaris lumbricoides: an overview of therapeutic targets. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2010 Oct 1;10(5):349-67.

- ↑ Hong ST, Chai JY, Choi MH, Huh S, Rim HJ, Lee SH. A successful experience of soil-transmitted helminth control in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2006 Sep;44(3):177-85.

- ↑ Jiménez B. Helminth ova control in sludge: a review. Water Sci Technol. 2007;56(9):147-55.

- ↑ Tsuji, N.; Miyoshi, T.; Islam, K.; Isobe, T.; Yoshihara, S.; Arakawa, T.; Matsumoto, Y.; Yokomizo, Y. Recombinant Ascaris 16-Kilodalton protein-induced protection against Ascaris suum larval migration after intranasal vaccination in pigs. J. Infect. Dis., 2004, 190(10), 1812-1820.